Everyone knows what affordances are. An affordance is an opportunity for action. It arises when you have three things:

- Structure in the environment that has properties.

- An animal that has skills or abilities.

- A relation between (1) and (2) such that the animal is able to act on the structure.

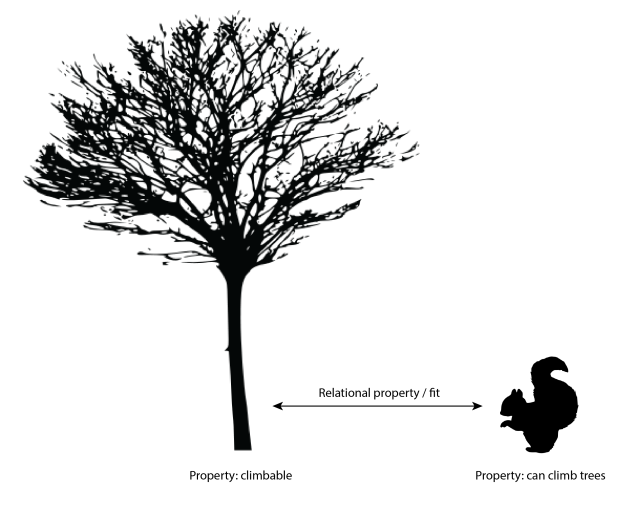

Let’s put that in a picture. Everyone likes pictures.

An affordance involves an animal, some structure in the environment, and a relation between the two

Now, there’s a slight issue that arises here, and it’s this: which bit of the diagram is the affordance? Well, sometimes the affordance is the thing that is denoted by the label under the tree, i.e. it’s a property of the tree such that the tree is climbable. At other times, the affordance is the two-headed arrow in between the tree and the squirrel, i.e. it’s the relation, or the fit between this particular squirrel’s abilities and the relevant properties of the tree. Jimmy Gibson, who invented the word affordance, was a bit inconsistent about this. This is unfortunate, but we’re just going to have to live with it.

What makes the concept of affordances so compelling is that it overcomes the old dualism between mind and body that’s been a feature of Western thought since thinking was invented by the Greeks. For thousands of years, meaning was something that happened in a cave. The concept of affordances liberates meaning from the cave, and releases it into the environment. Meaning, says Gibson, is real. It’s as real as apple pie or dolphins. Meaning consists in the fit between an animal and its environment.

Now, Gibson was careful to insist that what he was developing was an approach to perception. And he was designing this approach to perception in such a way that it would be general enough to apply to all perceiving animals. In suggesting that meaning is external to the perceiver, Gibson was not talking about linguistic meaning. The squirrel, in perceiving the tree, does not need to be able to say to itself: ‘Oh look at that tree. I bet I could climb that.’ The meaning, to repeat, is in the fit between the structure of the animal and the structure in the environment.

That’s what affordances are. The theory of affordances offers a new theory of meaning—an ecological theory of meaning that is new to Western thought.

And yet there’s a temptation to think that the concept of affordances can do more than this. Surely—so the thinking goes—affordances must be able to do more than merely pick out things like tree–squirrel complementarities? Surely there must be a way that we could extend the concept of affordances? Couldn’t we use it to explain human things like—oh, I don’t know… Like table manners? Or queueing? Or counterfactual reasoning? Gibson himself seemed to encourage this (1979, 128):

The different objects of the environment have different affordances for manipulation. The other animals afford, above all, a rich and complex set of interactions, sexual, predatory, nurturing, fighting, playing, cooperating, and communicating. What other persons afford, comprises the whole realm of social significance for human beings. We pay the closest attention to the optical and acoustic information that specifies what the other person is, invites, threatens, and does.

This passage makes things sound ever so straightforward. Humans, we are reminded, are nothing more than a special case of animals. Why can’t we just treat the human environment in the same way as we treat the squirrel’s environment? Culture is like a tree that we can climb up.

Well, maybe. But what would that mean, exactly?

There’s a paper in press at Behavioral and Brain Sciences that tries to extend the concept of affordances to culture. Me and Tony Chemero wrote a commentary on it (preprint here). In the commentary we suggest that the prospect of an empirical program based on ‘cultural affordances’ is not a promising one:

In practice, it has proved remarkably difficult to leverage [the concept of affordances] as part of a fruitful empirical program, even when the target of explanation is a single actor performing a simple task … It is much more difficult to apply the concept to culture, and to our knowledge no one … has succeeded in doing so non-metaphorically. You can say ‘cultural affordances’ all you want, but that does not constitute an empirical research program.

There’s a deeper problem than this, though. The deeper problem is that affordances, by definition, pick out a fit between a particular (individual) animal and its environment. But culture isn’t a fit between an individual and the surroundings of that one individual. Culture is a property of social collectives inhabiting a set of geographic places. If we want to be able to explain specifically human behavior, then we will need to reckon with the structure of the collective setting. This structure may be dynamic, only revealing itself over time. The point is that the relevant structure is a property of the setting, and it inherently involves multiple actors. It is not a property of the fit between an individual animal and its surroundings. To talk of ‘cultural affordances’ is, in that case, to commit a category mistake. It is to seek an explanation at the individual scale of a phenomenon that occurs at the collective scale.

Let’s consider an example. Take table manners. Question: Why do you not put your elbows on the table when you’re dining with the vicar? Answer: because it’s rude. Or, at any rate, because you’ve been told that it’s rude. It’s not that the table doesn’t afford leaning-on-with-one’s-elbows. It’s that leaning on the table with one’s elbows is not the done thing in this particular setting. The setting is causally relevant here, and it ought to figure as part of the explanation.

But hold on. Suppose that I simply want to explain your behavior in this situation—you as an individual. I could say that you are appropriately responding to the affordance don’t-put-your-elbows-on-the-table-when-the-vicar-is-around-ability. I wouldn’t be wrong to say that. It’s just that this affordance-based account doesn’t explain anything that wouldn’t be equally well (or better) explained by stating that the reason you don’t put your elbows on the table is because you are being polite. The language of affordances isn’t adding anything to the explanation here.

It’s reasonable to want to pursue an embodied account of human meaning—one that builds on and is consistent with Gibson’s account of perceiving and acting. We argue in the commentary that doing so will require us to adopt an appropriate account of human social learning—namely, Vygotsky’s account. What’s not good enough is to say: ‘Culture—why it’s all just affordances!’ As if that solves anything. As if being a cultural animal is no different, really, than climbing a tree.

At the risk of stating the obvious… Culture is not a tree. And you, dear reader, are not a squirrel.

References

- Baggs, E. and Chemero, A. (to appear). Thinking with other minds. [Commentary on Veissière, S., Constant, A., Ramstead, M., Friston, K., and Kirmayer, L. (in press). Thinking through other minds: a variational approach to cognition and culture]. Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

- Gibson, J. J. (1979). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Houghton-Mifflin.